PUBLIÉES PAR RAQUEL

52, av. Pierre Brossolette — 92240 Malakoff __ N° 3 — Juin 1990

CHARLES BERNSTEIN

on

CHARLES REZNIKOFF

Du 29 septembre au 1er octobre 1989 se sont tenues les Ve Rencontres internationales de Royaumont, consacrées aux poètes objectivistes américains (1). Parmi les intervenants venus des États-Unis, outre Carl Rakosi, Michael Palmer fit la présentation générale du « mouvement » objectiviste, Lyn Hejinian présenta Louis Zukofsky, Michael Davidson parla des « silences de George Oppen » et Charles Bernstein donna, sur Charles Reznikoff, la communication que l’on lira ici, ponctuée par des traductions « sur le vif » de Pierre Alféri. La transcription de la bande enregistrée de cette intervention a été assurée par Judith Crews. Je remercie Charles Bernstein d’avoir autorisé sa publication dans NOTES. R.L.

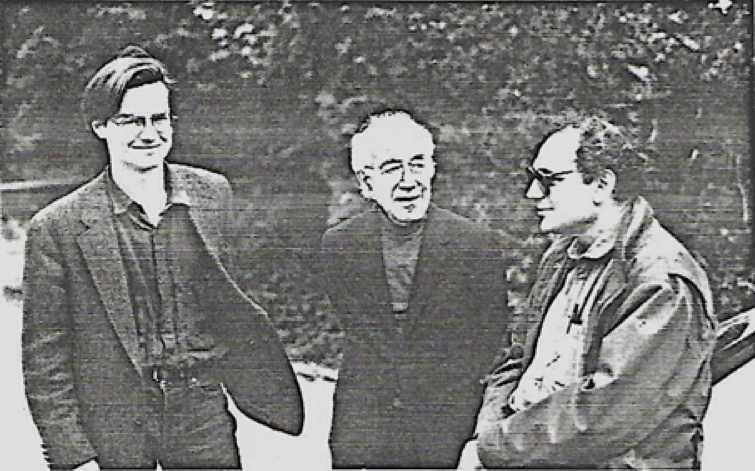

Royaumont, le 1er octobre 1989. De gauche å droite : Pierre Alféri, Carl Rakosi et Charles Bernstein.

Royaumont, le 1er octobre 1989. De gauche å droite : Pierre Alféri, Carl Rakosi et Charles Bernstein.

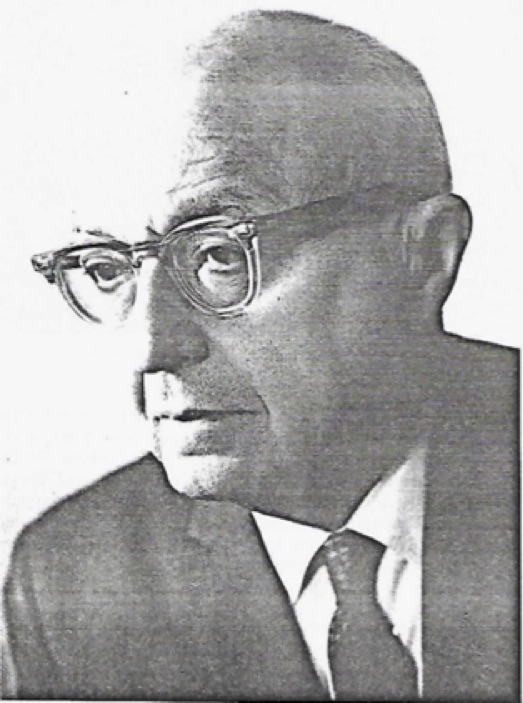

Fils d’immigrants juifs venus de Russie, Charles Reznikoff est né â Brooklyn, en 1894. Il est mort à New York, en 1976. La presque totalité de son œuvre poétique et romanesque a été publiée, aux États-Unis, par Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara. De Charles Reznikoff, on peut lire en français : Témoignage (États-Unis 1885-1890), trad. Jacques Roubaud, P.O.L./

Hachette, 1981. Le musicien (roman), trad. Emmanuel Hocquard et Claude Richard, P.0.L. 1986. Holocaust, trad. Jean-Paul Auxeméry, Dominique Bedou Éditeur, 1987. Des poèmes extraits de Testimony Volume 2, trad. Jean-Paul Auxeméry, in Banana Split, Numéro 36, 27, av. du Prado, 13006, Marseille.

Charles Bernstein est né à New York, en 1950. Il a dirigé, avec Bruce Andrews, la revue L=A =N=G=U=A=G=E. Poète, essayiste et traducteur (Claude Royet-Journoud, Olivier Cadiot), il est l’auteur d’une vingtaine d’ouvrages publiés aux États-Unis. On peut lire, de lui, en français, des extraits de Stigma, trad. Claude Richard, in 21 + I poètes américains d’aujourd’hui, Éditions Delta, Université de Montpellier, 1986

Royaumont, 30 September 1989

Charles Bernstein: We’re going to play just a brief bit of a tape from 1974. This would have been a tape made of Reznikoff reading at San Francisco State when he was 84 years old. It strikes me, hearing Carl Rakosi last night, that this kind of remarkably exuberant reading, for these poets who continued right until right through their lives, to do their work… It’s too bad we don’t have a tape of any of these people when they were quite young and starting to work as far as I know … because you may be getting a different sense, because in this tape Reznikoff is reading work that he wrote in the 1920s and even before that, and presumably it has a different twist to it. On that tape, interestingly, George Oppen does an incredibly enthusiastic introduction to Reznikoff and so as an introduction, again, I’ll just also say a few words biographically about Reznikoff so we’ll have three introductions: but perhaps the Oppen is the most useful on the tape. Just let me a few brief facts about the life of Charles Reznikoff, because I realized, talking to people this morning, while I’m ready to plunge into a commentary on Reznikoff assuming extensive knowledge of his work, perhaps I have to pull back a little bit from that, assuming that for many of you it would be an introduction.

Pierre Alféri : Charles Bernstein annonce qu’il va passer une bande vidéo où on voit une lecture faite par Reznikoff : il avait 84 ans. C’est une lecture qui a eu lieu à San Francisco et il est présenté sur cette bande par George Oppen. Charles Bernstein préfère donc que cette introduction soit faite par George Oppen, mais il va nous donner quelques détails biographiques concernant Reznikoff.

Charles Bernstein: It’s worth noting that Reznikoff was born in 1894; compare that to T.S. Eliot who was born in 1888 we’re just past the centennial; Gertrude Stein, who was born in 1875; Pound was born in 1885. You have in the 1880s, essentially, with the exception of Stein in 1875, a whole group of what one thinks of – what I would call – the ‘radical modernists’, fitst generation, also painters and so on. Reznikoff is older than the other Objectivists that we’re focusing on here, and the kind of larger group of poets that Michael Davidson, Michael Palmer and I mentioned yesterday, and I think his role as being somewhat older is recognized by his colleagues. He was already working at the time – he in fact could be compared to Williams, as much as to Zukofsky, for example, both in terms of age and the nature of his work. Williams was born in 1883, only nine years different, and Zukofsky, who was born in 1903: he’s about midway in that sense between Williams and Zukofsky, and I think it’s actually a useful way to think about what he does, not that chronology is destiny. Now we’ll see if Pierre can get those dates right.

Pierre Alféri : Eh bien, c’est très simple : Charles Reznikoff est né en 1894.

Charles Bernstein: Reznikoff’s parents came from Russia, because of the pogroms, and they came to New York City – along with many, many other people, including my own grandparents. There’s one interesting biographical story which I think I’ll just relate, because it’s sort of an interesting thing that he relates a lot, which is that his grandfather, I think it would be his mother’s father, when he died papers came back – a box of papers, reams of papers – written in Hebrew verse, and the family was upset that this might be subversive material – and I say ‘sub-verse-ive’ with the pun intended – and therefore burned the work of Reznikoff’s grandfather – the Hebrew verse. And Reznikoff mentions this in a poem, in an interview, and in the poem he suggests that perhaps whatever is left of this Hebrew verse of his grandfather is transmitted through him. He self-printed all of his work, and this again differentiates him from most of his contemporaries, I don’t mean just simply the Objectivists, but in general. He bought a press himself, and – actually the books are beautifully printed, they’re lovely to hold in your hand – and he basically printed them all; then he founded the Objectivist Press with some of his colleagues, and they together printed a book of Williams, which was a remarkable success – they were all surprised about that, and a book of his own, and of course the other Objectivists. But throughout his life, even after that, a couple of times a bookstore printed one of his books, and the Objectivist Press printed one of his books – he basically continued to print his books himself, and to give them away for free. When there was an error he would painstakingly hand correct each one. He never – I always mention Reznikoff when people talk about self-publishing, because in many ways it’s the best way to get your work out, not to have to worry about dealing with a kind of nexus of what publishers think, or somebody else, just to simply put it out, and Reznikoff doing that throughout his life is a wonderful model of what that could be. Of course at the same time it does represent a disturbing neglect of his work, for many years. People ask what brought the Objectivists together, and of course there are obvious differences between them, in terms of their work, but the fact is they read one another and were, to some degree, even with some differences of opinion, as we know about, supportive of each other in the sense that they acknowledged each other as poets working together, and that was a small circle, a pool of light in a world of poetic darkness, I think, for some of them, in terms of the reception of their work. So he had the few people he would give these books to, and he would read the books in turn. Even Williams – in, again, to me an incredibly kind of disturbing letter that he writes to Reznikoff, late in his life, after his stroke, he says, ’You pressed on me – ’now this is Williams, whom he published, who is the person you’d think would be in close touch with him, and whose work, I would say, his work most resembles, I mean I think the two of them have an interesting relationship – wrote to him saying, ‘You know, I never before read the book that you gave me, some 20 or 25 years ago, and I just want you to know that it’s one of the most remarkable and amazing things that I’ve ever seen.’

Pierre Alféri : La famille de Reznikoff est venue de Russie au tout début du siècle pour fuir des pogroms. Après la mort de l’un des Grand-pères de Reznikoff ils ont reçu une malle remplie de poésie en hébreu, dont ils ne savaient pas quoi faire et qui les a un peu effrayés, parce qu’ils craignaient qu’elle soit subversive. Et Charles Bernstein dit que Reznikoff assuma une tâche un peu parallèle å cet héritage en commençant ã imprimer des livres, puis en continuant toute sa vie à s’imprimer lui-même. Les premiers livres de l’Objectivist Press étaient un livre de Williams et un autre de Reznikoff. Par la suite, il a lui-même édité ses textes ; il les a donnés, en général, plutôt que vendus, et il faisait même des corrections, quand il y avait des coquilles, à la main sur chaque exemplaire. C’est, selon Charles Bernstein, une sorte de modèle d’autopublication ; un des intérêts du groupe Objectiviste, en ce sens, était qu’ils se soutenaient mutuellement, se lisaient mutuellement et se publiaient mutuellement tout en restant largement inconnus. Et à ce propos il raconte

une anecdote, de la fin de la vie de Reznikoff et de Williams, où Williams a écrit ã Reznikoff pour lui dire qu’il n’avait pas lu un des livres que Reznikoff lui avait envoyé depuis vingt ans ; il venait de le lire, et qu’il trouvait le livre remarquable.

Emmanuel Hocquard : Je voudrais juste, pour l’anecdote, rappeler que les premiers livres de l’Objectivist Press ont été publiés en France, près de Toulon, et que ça avait posé des problèmes pour leur diffusion aux États-Unis parce qu’ils n’étaient pas reliés mais simplement brochés. C’est assez amusant. Et, à propos de cette histoire de malle contenant des poèmes en hébreu hérités d’un ancêtre (je crois bien qu’il s’agissait du père de la mère de Reznikoff ; et que c’est la mère de Reznikoff qui a brûlé ces poèmes de peur que les services de l’immigration, ou d’autres, tombent dessus), il m’est revenu en mémoire un poème, très court, de Reznikoff, que je ne résiste pas au plaisir de vous lire. Voici.

Mon grand-père mourut, longtemps avant ma naissance

parmi des étrangers ; et tous les poèmes qu’il écrivit

sont perdus —

sinon ce qui parle encore à travers moi

comme si c’était moi. (trad. Jacques Roubaud)

Charles Bernstein: It’s been suggested, of course, that this image of the burning of the work, is one, as I said, of the motivations for his self-publishing his work. It should be emphasized, and Lyn can speak to this better than I can, that he learned to be a letterpress printer to do this. That means he handset each letter, and printed each page separately; this is a far cry from getting an Apple computer and printing it out on a laser printer.

To conclude ‘Charles Reznikoff, His Life and Work: an Introduction,’ he did go to law school. I pondered this for a while, to think how could his parents have been so successful – they were in the millinery business – that means hats – but in fact they didn’t contribute toward his going to law school, it was not expensive in those days, and he claims to have been walking by the NYU Law School, and remembered that Heinrich Heine had gone to law school, and thought that perhaps this was a good occupation for a poet. And I think Heine is a very interesting model for Reznikoff, in some ways. But he never practiced law. He was never interested in practicing law, he didn’t want to spend his life doing that: he was interested in the process. He did work as a legal abstracter, in fact his life-work patterns resemble that of my contemporaries more than many I can think of – he did editorial work for various publications, including one that his wife, a very-well-known-in-the-Jewish-community Zionist organizer, Marie Syrkin (who just died last year) edited. But he worked as the managing editor, not being allowed to intervene editorially in that work. So it was work he didn’t enjoy very much. He did not wish to work, but had to. And as to his leftism, again he was very much a loner, but he does say in his one poem about Marx – much of his work is about those left out of society, those whose lives were destroyed by things beyond their control or things very much within the control of the economic system that he lived under, and he has a poem to that effect entitled ‘Marx.’ But that’s about the closest he comes to any specific political comment. But it’s hard to read his work without an overpowering sense of the political, and his work, again, because Emmanuel did say that in the French, is collected not completely because there are plays and other things that he wrote, novels and so on, but the poems are collected in this two volume

set that Black Sparrow did, and the two-volume Testimony – taken from legal documents from 1885 to 1915, which he condensed and rewrote, often looking at hundreds of pages of documents to get one short poem. And certainly one of the great epic poems of the 20th century in America, widely unknown, because of that. Reznikoff, unlike Rakosi and Oppen, continued to write through the 1930s, and actually Testimony is written pretty much in the period where both of them stopped, and I think that has to do with his greater sense of solitariness and self-commitment to poetry and some of these other things I’m mentioning. But it’s interesting to note that if you think about that really remarkable lacuna in the work of Rakosi and Oppen, which I think anybody following this work has to think about, it’s interesting to think about Testimony as being Reznikoff’s response to that, and what he would do, to spend his whole day, really, in the library after working – he had a job, he worked, but he spent all his free time – he had a wife, he didn’t have children, his wife was not always living with him, she was teaching at Brandeis for a while, and this is really what he spent his life doing. And then after the translation go right to 0ppen introduction on that tape.

Pierre Alféri : D’abord Charles Bernstein a ajouté qu’il pensait en effet que la peur, le souvenir de l’œuvre du grand-père brûlée expliquaient en partie le désir de Reznikoff de se publier lui-même. Puis, pour en terminer avec les indications biographiques, il a rappelé que Reznikoff a fait des études de droit, là il y a eu une anecdote que j’ai pas.... que j’ai pas bien comprise... (Aparté inintelligible concernant le commerce de chapeaux des parents de Reznikoff.) Ensuite il a fait des travaux d’édition, en particulier pour une organisation sioniste que sa femme dirigeait, je crois, ou bien où elle travaillait, mais ces travaux ne l’intéressaient pas beaucoup, c’était seulement pour gagner sa vie. Il était très à gauche, politiquement. Charles Bernstein a donc montré les principales publications, les Collected Poems d’abord, dans l’édition Black Sparrow, et Testimony. À propos de Testimony, il a expliqué que Charles Reznikoff a fait un travail énorme pour cette œuvre, puisque chaque poème suppose en fait une lecture et une compilation préalables de documents, et il y consacrait tout son temps en dehors de son travail dans une biblio – thèque, pendant de très longues années. Charles Bernstein a suggéré que, au moment même où Carl Rakosi et George Oppen s’arrêtaient d’écrire pour des raisons dont on a parlé hier, en particulier politiques, qui tenaient à leur rôle dans la société, le travail de Testimony était, d’une certaine manière, une réponse à ces difficultés mêmes, puisqu’il était à la fois, puisqu’elle touchait l’histoire de la société américaine directement, et que c’était à ce titre une véritable épopée américaine, particulièrement saisissante et justement pour cette raison, très peu connue en Amérique.

Charles Bernstein: David Bromige is asking was he not in Hollywood, and that, of course, is fascinating – he wrote The Manner Music about that. He had a friend who was a very successful Hollywood producer, and brought him out to Hollywood and it’s again a boggling thing to imagine him in Hollywood – nothing about him suggests that he could have done this. I-le’s not like F. Scott Fitzgerald, drinking away, and trying to make it. He had great ideas, none of which were acceptable to the studios, he kept thinking you could rewrite these films in ways that would be more interesting, and he was right, I’m sure! One of his most famous poems about that is sitting in his office, watching a fly buzz around, suggesting that he had little to do there … but he was well paid. He also worked as a sales person in his father’s millinery business, which he liked actually, because he used to have to sit around waiting for the buyers … which gave him time to think. He preferred that to working as a lawyer.

Pierre Alféri : David Bromige a rappelé que Charles Reznikoff avait aussi travaillé à Hollywood. Charles Bernstein raconte en effet qu’il avait un ami producteur, qui avait beaucoup de succès à Hollywood, et qu’il avait beaucoup de travail là-bas. Il eut d’abord beaucoup d’idées de scénarii, très intéressantes, très bonnes, mais aucune n’a été retenue. Il passa donc beaucoup « de temps à ne rien faire en étant très bien payé. Il y a un poème qui fait allusion à une scène où il est à son bureau en train de regarder voler une mouche. Il a aussi travaillé chez son père, dans une entreprise de chapeaux où il prenait des commandes, et ça lui convenait très bien parce qu’il se contentait d’attendre les clients.

Emmanuel Hocquard : J’aurais juste à ajouter un mot à l’appui de ce qui vient d’être dit. Dans son roman posthume, Le Musicien, il y a justement l’évocation de ce passage à Hollywood, une satire extrêmement féroce de ce milieu superficiel et épouvantable d’Hollywood. Le Musicien, qui est en partie autobiographique, se situe dans la période de la Grande Dépression américaine. C’est un témoignage extrêmement précieux non seulement sur les difficultés, la pauvreté, le chômage, etc., mais également sur la montée de l’antisémitisme aux États-Unis, chose qui est quand même assez peu connue à l’extérieur.

THE TAPE BEING PLAYED: George Oppen is speaking: ‘That poem by Charles that begins, “As I, barbarian, at last, although slowly, could read Greek/ at ‘blue-eyed Athena…’ and it goes on, is Charles” reading of that lithograph portrait on the wall of Athena. Just take that poem, it’s a beautiful poem, with a great cadence, and it moves on into that strange feeling of visiting famous times and famous places, in the midst of one’s own affairs through books. There doesn’t seem any reason… That poem was written at least 40 years ago, since I read it 40 years ago. I’m complaining about the length of time it has taken to notice Charles Reznikoff. Not that Charles Reznikoff so far as I know cares. The last time I tried to praise Charles to himself he at once interrupted to say, “George, I’m sure we both do the best we can.” A difficult man to praise, and this is my opportunity. And all the same that isn’t just random eccentricity on Rezzi’s part, and if it was modesty, it was modesty of extraordinary force. Rezzi wouldn’t listen to praise because he intended to disregard condemnation, and this was… Some of his poems in the Collected were written in 1918, some of them earlier, I think. There was the issue of free verse, to begin with, and, of course, Reznikoff couldn’t make use of the Whitmanesque breadth of the Midwest poets, and he didn’t have the authorization of the New England scene. These were poems of the city. Instead, a small man starts to climb the stairs out of the subway, and he sees the moon shining through the entrance, whereupon the world stops, and is illumined. Poem after poem of the city, which is experienced as the narrow end of the funnel: there are poems of the metaphysical dimension, actually; the “metaphysical dimension” being the absence of terror, or the disregard of it down to the very chewing gum stuck to the pavement which is in that poem. The narrow end of the funnel in the poems. The proofs in these poems are images, and the images are proofs, and the proofs are overwhelming. But Rezzi, who didn’t permit praise and disregarded condemnation, had bought a letter – press, every evening after work he set two lines of verse, teaching himself to set type as he worked – I said, Rezzi wouldn’t listen to praise because he intended to disregard condemnation or neglect. He had bought a letterpress, and every day, every evening after work Reznikoff set two lines of verse, teaching himself to set verse as he worked at it, and this way he printed all of his first books by himself. We, Mary and I that is, have carried these poems in our minds through everything that has happened to us since we were 19 or 20 years old. I don’t know of any poems more pure, or more purely spoken, or more revelatory. As I’ve confessed before, I think the young of my generation were

luckier than the youngest in this audience, in that we had to go searching for our own tradition and our own poets. What we found was Reznikofffl’ and he’s played – I cannot say how important he has been to us, and I think he will be to you, and this is what I wanted to say to Charles Reznikoff when he said, ‘George, I think we all do the best we can.’ (applause)

Reznikoff: If I’m not loud enough, tell me, I’ll try to be louder. To begin with, I thank you very much, George, for your introduction, except that it embarrasses me, now I have to deliver. If you had been very hostile, I think it would have been stimulating. Thanks, anyway!

I think I’ll begin in a way I usually do, with my platform, to use a political expression, my platform as a writer of verse.

Salmon and red wine

and a cake fat with raisins and nuts:

no diet for a writer of verse

who must learn to fast

and drink water by measure.

Those of us without house and ground

who leave tomorrow

must keep our baggage light:

a psalm, perhaps a dialogue –

brief as Lamech’s song in Genesis,

even Job among his friends –

but no more.

Like a tree in December

after the winds have stripped it

leaving only trunk and limbs

to ride and outlast

the winter’s blast.

That’s one, and now I’ll read you another one:

I have neither the time, nor the weaving skill, perhaps,

For the intricate medallions the Persians know;

My rugs are the barbaric fire worshippers:

how blue the waters flow,

how red the fiery sun,

how brilliant a green the grass is,

how blinding white the snow.

That’s the platform! (applause)

Please don’t applaud! Because I won’t be able to say all I want to say, and that’ll stop me! Well, anyway, let’s go on from here. I – of course most of the poetry of the last century and of this century too, has been properly called ‘nature poetry’. And the last great poet was Robert Frost, in that class. But for us who are born in cities – at least I was – and lived there all our lives – well, that’s a very appropriate comment, but I’ll have to wait a while – END OF VIDEOTAPE).

That’s a wonderful reading. Those who wish to listen to the whole thing, it’s about 45 more minutes, and really in a certain way the best introduction to his work, better than what we might add or detract here. Listening to this reading and being struck by what he had done I went back and created this text, and to create this text, I had to go through the two volumes, following from the first lines, and Xerox the page and cut out the little bits and strips, so that I had a whole series of little tiny papers and bigger papers numbered with the page numbers where they were and reconstruct the reading that he gave, which would go from 1918 to 1950 to 1920 to 1935, back and forth, through this intricate weave, not as the Persians make, as he says, but as Reznikoff makes, and by doing that, by cutting these strips out, I was struck with what exactly was the process of serial composition that he was engaged in all his life, which I think, needs to be said almost first, when reading the work. And what I mean by that is, this is a process of collage, of disjunctive collage, of different pieces and bits, ordered in a particular sequence and numbered, from the very first work that he did, Rhythms, in 1918, we have here – and you can see it on this page, sometimes it’s just two lines, then four lines, poems, very tiny poems often, numbered, numbered, to give a sense that there is a sequence, but the sequence is not constructed by some type of ordering principle outside of the compositional process, not by narrative, not by historical sequence, not by any type of logical or causal progression, at least overall. Sometimes one poem will deal with the subway, and the next one will deal with the subway, and then there’ll be something else. There’s different types of thematic, musical and other kinds of juxtapositions, tonal, going on, but it’s a musical working with collage and juxtaposition, a kind of montage of various sorts of elements that are put into sequence that bring to mind many subsequent workings with the idea of seriality and sequentiality that we have in American poetry, which in many ways at a formal level do not transcend the actual innovation that Reznikoff worked on right from the first, which was this type of disjunctive, serial collaging, and I would think if one thinks of the idea of the serial poem in Jack Spicer, or Robin Blaser, one gets one instance of that; if you think of what Ron Silliman has called ‘the new sentence,’ you get another instance. Silliman taking individual sentence units and finding different ways to permutate them, based, in his case, on mathematical formulas and so on, but the basic impulse towards collage, and therefore the issue of the relation of the part to the whole, the shot to the sequence, surface to depth, becomes apparent here. So this again, is an example of one of the most innovative realizations of parataxis in radical modernism, and brings to mind his great contemporaries Stein and Williams.

Pierre Alféri : Charles Bernstein remarque surtout, dans cette lecture et dans le reste, puisqu’on en a entendu seulement une toute petite partie, que Charles Reznikoff lit des poèmes de périodes très différentes sans respecter l’ordre chronologique et que cette technique, cette opération est constante chez lui : une opération de collage, si on fait une analogie avec les techniques visuelles du collage ou du montage ; et il le fait également dans la façon dont il publie ses poèmes, puisque il lui arrive de publier des poèmes extrêmement courts qui sont simplement numérotés et dont la suite ne répond pas, à une première lecture, à un ordre causal, ou thématique, mais simplement à un numérotage, donc à un montage. Et c’est toute la question d’une écriture en série, en séquence, c’est-à-dire d’une écriture où les éléments peuvent se redistribuer dans un ordre différent, comme dans cette lecture, où ils sont soumis à des permutations. Charles Bernstein suggérait que beaucoup de choses qui avaient été faites ensuite autour de ces techniques n’étaient pas fondamentalement novatrices par rapport à ce que faisait déjà Reznikoff ; il pense, par exemple, à Jack Spicer et à Ron Silliman, qui a produit une théorie de la phrase où des permutations sont possibles selon des formules mathématiques. C’est tout un jeu sur l’opposition à la fois de la partie et du tout, de la prise de vue de l’image et

de la séquence, de la surface et de la profondeur, donc un jeu sur la juxtaposition ou la parataxe qui correspond à la juxtaposition dans la phrase.

Charles Bernstein: Because of limited time, I simply will have to suggest a series of possible ways to look at these things further, so just take them as thoughts to fill in yourself later. By surface/depth, I think Reznikoff was not interested in a certain kind of realist or mimetic depth that would occur if you thematically linked all of these different items, and I think one of the reasons that his work could not be understood so easily, even compared to ‘The Waste Land,’ and I would compare ‘The Waste Land’ to Testimony in many ways – the radically different ways of dealing with dystopian material – is that by constantly intercutting and jump-cutting between the materials, the status of the detail and the particular gains primacy as opposed to some level of rhetorical depth and narrative closure, which is added to even within the kind of larger collage formats that were articulated by some of the ‘Cantos’ and by ‘The Waste Land.’

Pierre Alféri : En comparant ces techniques avec celle de « The Waste Land » d’Eliot, qui était un exemple qui avait beaucoup frappé à l’époque, de juxtaposition, de passages apparemment très hétérogènes, ou même avec les techniques utilisées par Pound, Charles Bernstein remarque que ce que cherche Reznikoff, ce n’est pas, comme dans ces exemples, ã obtenir une profondeur thématique par la juxtaposition de passages qui sont analogues ou qui ont un rapport thématique. Ce qui l’intéresse dans cette technique c’est plutôt le statut du détail qui lui est associé et qui est tout à fait particulier à son écriture.

Charles Bernstein: There’s no one who was more forceful in poetic work in foregrounding the detail and the particular over and against the blending of those details into some larger form. And that’s what I think those numbers represent in those poems. It’s not that they don’t add up to some larger form, but that the detail has an integrity and a particularity to itself. This is an idea that exists in many of Reznikoff’s contemporaries, but I think in many ways he was the most militant about it, in his own, in some ways very non-didactic way. It’s the combination of militance and extreme non-didacticism that’s one of the’ great characteristics of Reznikoff – and I would call that just for the purpose of tin – ding a term, the invention of literary cubo-serialism in American poetry. In this sense, the subject matter in Reznikoff is literally beside the point of this formal innovation, which would be possible even with different subject matter, and even without explicit subject matter. And this is a point that would of course offer a different reading than some of the readings of Reznikoff which like to take him as the most conservative and accessible of the Objectivists, and in fact as a kind of literary realist, which would – if that’s taken, be very much outside of the context that anyway some of us are presenting for the Objectivists here. I’m suggesting that to understand Reznikoff you can’t take one of these little poems as if they existed in isolation and say that this is what it’s about. You must consider the seriality of the work, and that that is fundamental, even more fundamental, if one has to make the distinction at all, than the subject matter, as impossible as that is to say in some way.

Pierre Alféri : Le statut du détail est extrêmement particulier chez Reznikoff, et il prend un relief tout à fait unique, qui fait que la mise en série des poèmes et leur numérotation ne correspondent pas du tout à la volonté d’intégrer les détails dans un tout ou dans une grande forme, mais au contraire de les isoler et de les maintenir séparés. Par opposition à un simple réalisme littéraire, Charles Bernstein préfère appeler cette technique une sorte de « cubo-sérialisme » ou de » sérialisme cubiste, » qui serait une innovation. De ce point de vue, selon lui, le sujet du poème, le propos, n’est pas véritablement l’essentiel, bien qu’il soit très important, mais, aussi difficile à penser que cela puisse paraître, l’essentiel

est ici dans la série elle-même et dans la forme sérielle ou séquentielle que prennent les textes.

Charles Bernstein: To pursue a little bit what I was trying to suggest last night about perhaps not the Jewish themes in Reznikoff but a Jewish sense perhaps of the holiness of the everyday, the holiness of witness, I think, what exactly is the status of the particular and the detail in Reznikoff? What is the status of the particular? Why is that important? You have that in Williams, you have that in Zukofsky, you have it in Rakosi – and I’m not meaning to suggest that any of the things I’m saying about Reznikoff doesn’t apply to other people by the way, I think it does – but, focusing on Reznikoff, it seems to me one has the idea, for example, in Baal Shem Tov, certain Hassidic notions of the holiness of the everyday, the holiness of the most common acts, the most base acts, the most vulgar acts, the holiness of walking, the holiness of drinking, the holiness of sitting, the holiness of talking, the holiness of looking, the holiness of touching. If you listen to the epilogue of Allen Ginsberg’s great poem ‘Howl’, where he has a litany just like what I just gave you: ‘holy asshole, holy armpit, holy nose,’ etc. (I would argue that Ginsberg’s three major influences are Reznikoff, Whitman and Blake, an interesting trio), is I think getting this from a close reading and understanding of Reznikoff in the sense of making those details – in other words I’m just trying to suggest what the status of the data is, and raise this way of looking at it. Blessedness would be another term for that.

Pierre Alféri : Il faut mettre en rapport avec ce statut du détail les thèmes juifs de l’œuvre de Reznikoff et, avant tout, l’idée de sainteté juive, par exemple dans la conception de Baal Shem Tov qui est liée à la quotidienneté, c’est-à-dire, la sainteté des actes les plus quotidiens, manger, parler, s’asseoir, etc., ou encore, à ce qu’on peut dire en anglais : « blessedness. » On ne peut pas traduire ça en français, le fait d’être béni. À ce propos, Charles Bernstein rappelait la fin de « Howl, » le poème de Ginsberg, où il y a justement une série d’affirmations, de sanctifications de choses basses, vulgaires, ou habituellement perçues comme telles. D’ailleurs, une des influences de Ginsberg est Reznikoff, avec Whitman et Blake.

Charles Bernstein: This idea of blessedness or holiness of the everyday is a sharp contrast to an orthodox religious view – orthodox Jewish and otherwise – that ritual and certain types of ritual acts are separated out, such as today, Roch Hachana, being one of the holiest days of the year, from a Jewish point of view, would not be separated out, from last Monday, which would not have been a particularly hierarchical day. So all the more appropriate to hold an occasion like this on a day like this to emphasize the everydayness of every day. For Reznikoff, the relation of the observer to the observed it not static, with the observer on one side and the observed on the other, but is one of nearness. Reznikoff’s relation to the world through the use of the detail, through the use of the particular, is one of nearness to and dwelling within the world, and this concept of witness, then, is not a static legal conception of witness, the concept of testimony is not a static legal conception of testimony, but in fact a full-scale critique of juridical and authoritarian modes of control of witness and testimony that distance you from the world, and is in that sense a critique of the whole movement of distanciation and high irony that you see and is often associated perhaps in some ways simplistically with T.S. Eliot, but certainly with aspects of Eliot’s theories and Eliot’s followers.

Pierre Alféri : Cette conception du quotidien et de la sainteté du quotidien s’oppose aussi par exemple à la conception religieuse orthodoxe qui hiérarchise et marque le plus fortement possible la différence entre un jour sacré comme aujourd’hui, le jour de Roch Hachana,

et d’autres jours, alors que ce que fait Reznikoff suggère au contraire une conception non-hiérarchique des détails et de la quotidienneté de chaque jour. De ce point de vue, Charles Bernstein distingue cette conception du détail ou de la singularité de celle qui a pu être mise en relief par Pound et par l’Imagisme, la notion de « singularité lumineuse » chez Pound qui au contraire met en relief, exhausse, hiérarchise, pour les célébrer, les détails et les singularités. La conception qui se dégage de l’écriture de Reznikoff est plutôt celle d’un regard sans distance, sans distanciation active en tout cas, sans ironie, et qui s’oppose en ce sens à la distanciation mise en œuvre par Eliot dans sa poésie. Et là aussi il rappelait l’idée évoquée hier par Michael Davidson, qui vient de Whitehead, d’un rapport entre l’observateur et l’objet qui soit inextricable, où l’un n’a pas de véritable privilège par rapport à l’autre et où ils ne soient pas véritablement séparés.

Charles Bernstein: We can’t say ‘quotidien’ when we’re talking about this in English be – cause ‘quotidien’ is too French, too extraordinary a word to talk about the everyday, but it’s interesting to hear it translated as quotidien, which is a word that exists in English as well, because there’s been so much interesting written about the status of the quotidien in French philosophy, which I think is quite relevant to the practice of the Objectivists. I’m thinking of course of Lefèvre, but equally of Michel de Certeau, whose most recent work translated into English, Arts de faire, in French, is called The Practice of Everyday Life, in English, although arts de faire is in fact a better term for what Reznikoff is doing.

Pierre Alféri : D’abord, j’avais oublié une chose importante, je crois : à propos de l’idée de témoin, de l`idée du témoin juridique, du témoin légal, Charles Bernstein voulait faire une mise au point en disant que selon lui ce n’était pas du tout une conception statique et passive du témoignage légal, l’idée qu’on associe le plus facilement à cette situation, mais au contraire une conception active. Et il faisait la différence entre le terme « quotidien » en français, et le terme « everyday » (« de tous les jours ») qu’on utilise en anglais ; et il disait qu’à son avis ce qui avait été écrit par des Français, en particulier par Lefèvre, La critique de la vie quotidienne, et par Michel de Certeau récemment sur le quotidien, pouvait tout à fait aider à comprendre ce dont il s’agissait chez les Objectivistes.

Charles Bernstein: To give you a sense that I’m not totally imagining this in Reznikoff, I point out the top of the fourth page of the Xerox, the poem about paradise, where I think Reznikoff is suggesting that the paradisiacal, the dimension of paradise is to be found in the detail, in the everyday, in the common. And since Lyn Hejinian has actually written so much about this topic it actually fits in nicely with both her sense and also the Ron Silliman book Paradise, and I relate this view in fact to work of my own contemporaries. So this is the poem that’s number 20 on the top of page 4, and you’ll hear Reznikoff read it.

As I was wandering with my unhappy thoughts,

I looked and saw

that I had come into a sunny place

familiar and yet strange.

‘Where am I?’ I asked a stranger. ‘Paradise’

‘Can this be Paradise?’ I asked surprised,

for there were motor-cars and factories.

‘It is,’ he answered. ‘This is the sun that shone on Adam once,

the very wind that blew upon him, too.’

So here I’m suggesting an idea that for first-generation immigrants, such as Reznikoff, the entry into English, like the entry into the world, was not to be one of exile, and here I want to make a sharp contrast, although I think it’s a useful comparison, between the great French poet, or poet in French, I think would be better to make my point – Edmond Jabès, whose sense of exile marks a sharp contrast from the sense of inhabitation that Reznikoff worked with. And I think the fact is that America suggested to someone like Reznikoff a possibility for inhabitation in a way that France did not suggest for Jabès. For Jabès, presumably, Europe was already inhabited. For Reznikoff, America was not yet made. Was not yet made. And I would say, is still not yet made in his sense; that is to say, that’s the task, and, I would say to Carl Rakosi, that is the social function of poetry. Per – haps simultaneous that its esthetic function IS that social function. So, for Reznikoff, the task is to found America, to found an American English, and he becomes a finder in order to found, and so the use of found materials, which so pervades his work, and which is the basis of Testimony, his largest collection of work, his largest single project, composed simply of found materials, that he becomes a finder as founder to inhabit, one who makes a new language, a new world.

Pierre Alféri : Le poème qu’a lu Charles Bernstein, que je ne peux pas traduire, concerne le paradis, et il l’a lu parce que justement c’est une conception du paradis extrêmement quotidienne, il l’a rapproché des textes de Ron Silliman et d’autres. Dans ce poème, le paradis est un lieu qui comprend des camions et des usines. Quant au statut d’immigrant de Reznikoff, Charles Bernstein le distingue de la façon dont ce statut peut être vécu, mis en scène, par exemple, dans l’œuvre d*Edmond Jabès. Il ne s’agit pas vraiment d’un statut d’exilé pour Reznikoff, peut-être simplement en raison de la différence entre l’Amérique et la France pour un immigrant ; l’Amérique, pour Reznikoff, n’est pas un lieu déjà habité au même titre que l’Europe peut l’être ; c’est un lieu qui n’est pas encore fait, qui n’est pas encore achevé. Et donc le rôle du poète immigrant est un rôle de fondateur ; il s’agit de fonder l’Amérique elle-même et de la fonder justement à partir d’un matériau découvert. Le rôle du matériau textuel, du « témoignage », des documents qui sont utilisés dans l’œuvre de Reznikoff, peut se comprendre ã partir de là.

Charles Bernstein: Now, because I must stop now, I’ll just briefly summarize some of the other points that I would make, without elaborating. I think, therefore I read Reznikoff not in terms of the flatness or absence of rhetoric but in terms of a nearness to the world not seen as nature but as social, urban. The materials of the world at hand as found, words – and world – but words as materials, not, that is, reports of things seen, narrow definition of the Objectivists, but bearing witness to things not seen, overlooked, entering into the world as a dissent/descent, not an idealized assent/ascent. Testimony as witness in court, as opposed to what? Reznikoff says, not a statement of what he felt, but of what he saw or heard. The witness can’t say in a trial a man was negligent, which is a conclusion of fact, but how that man acted, says Reznikoff. So maybe less however a matter of sight, of occular sight, than of action, not static but dynamic, as opposed to a pre-processed conclusion. The active witnessing of Reznikoff is an unfolding, a reference to process, not of a static occular seeing. Nearness is an attitude of address, not isolated, de-animated, images of distantiated occular evidence, as in the subway poem, and that’s just this four – line poem on page 3:

Rails in the subway,

what did you know of happiness,

when you were ore in the earth;

now the electric lights shine upon you.

What I’m suggesting by the difference between a certain idea of flattened occular imagism and what Reznikoff is doing is particularly the address to ‘you.’ If it was to be a certain idea of what we might think of as an objectivist poem, he wouldn’t have – he would just say ’rails in the subway, WHO were once ore in the earth, ‘flat. But he’s addressing it and bringing himself close to it, and I think this address, this nearness, is what Michael Palmer was talking about yesterday by talking about an intervention, what I say is a witness that intervenes. I think if you read this work of these individuals, in the extended group, you see that it is not a fl at, occular kind of objectivism, of witnessing which would allow for a certain kind of binary opposition between the thing seen and the seer, or between words and things, that there’s a collapsing of that at a very sophisticated level, and I think my sense of nearness is to suggest that. The intimacy of address, the “foundling,” the “founding,” the FONDLING! that is to say the handling of the materials, the fondling of them, as if they were precious, the comment, the intrusion into the materials, is a nearing toward a dwelling, making a habitation. So again, the part of Reznikoff which is specifically not like haiku, and which he specifically distances himself from in terms of haiku, is the fact that he will add these comments, which in some ways people would say, seem to spoil the poems. He adds a little twist at the end, and I think this is this nearing toward the world, and not an attempt to put it at a distance, and again I contrast that with the distanciation and irony and so-called “high modernism”, or what I call “high anti-modernism.” Being apart – “a-part” – distance from language – taking back the language from its metaphysical, its symbolic distortions, yet swings back to the question of exile, as exile from Hebrew. Reznikoff says

how difficult for me is Hebrew:

even the Hebrew for mother,

for bread, for sun

is foreign.

Which is a Jabesien comment, in fact. “How far have I been exiled, Zion.” So some type of hidden language – he also talks about having married the language of strangers – there is that tension but it’s a tension that he wishes to collapse, not to accept, not to reify. So witness as care, as involved, as care taken, caretakers, care in the language, for the world; language as caretaker of the world: witness-testimony as self-cancellation, and that’s a term he takes from Zen, that he likes, Reznikoff himself: witness-testimony as self-’ cancellation so that the language event speaks of and for itself, suggesting a modernist autonomy, a forgetfulness of self, as Reznikoff quotes a Zen article. Testimony I see in terms of the structure of event, the constellation of detail, composed of details, so that the picture is produced by this method, not presumed; the nearness-unfolding of event breaks down the subject-object split; subject-object, observer-observed; the paranoia (next to the mind) of the objective depersonalized gaze. Here the dualities collapse onto one another; the distanciation-irony is collapsed; the observer enters into the observed through a process of participatory mourning. Thrown into the world through event as testimony, testimony as event, the poem merges objective-subjective, those two things. Event emerges as the world-word materializing process takes place. Testimony: to found America means to find it, which means to acknowledge its roots in violence, to tell the lost stories, because unless you find what is lost you can found nothing. ’We are a lost generation) says Reznikoff’s mother, about her generation. The founding gesture of the parent-immigrant generation: against the indifference of the juridical gaze, the paradigm of distanciation. Founding means giving witness to what is denied at the expense of the possibility of America. Testimony as memorial, an act of grief, grieving, of mourning, the cost of life, the cost of lives lost is poetic, psychic economy, of which this work is an account, an accounting. No

one to witness and adjust; no one to drive the car except here; calling the lost souls: O earth O earth return.

(Pierre Alféri : on va aller vite ! From Charles Bernstein: He has the text, by the way, so at least he doesn’t have to do it spontaneously!)

Charles Bernstein voit la poésie de Reznikoff non pas comme une poétique de la platitude, de l’absence de rhétorique, mais plutôt de la proximité — en fait le mot en anglais veut dire à la fois proximité et approche, à la fois actif et passif ; proximité du monde qui n’est pas vu comme une simple nature, mais comme un monde social et urbain. Et il s’agit de traiter un matériau du monde qui est à portée de main, donc dans le quotidien urbain tel qu’il est découvert, et les mots eux-mêmes sont le premier matériau. Il ne s’agit donc pas de reportages ou de comptes rendus de choses vues, ce qui serait une définition étroite de l’objectivisme, mais plutôt d’un témoignage concernant des choses non vues ou mal vues. L’entrée dans le monde se fait alors comme une descente (ou différence) et non pas comme une ascension (consentement) idéalisée ou idéaliste. Ainsi Testimony, où il s’agit de témoigner comme à la cour, comme dans un procès. Charles Bernstein se demande à quoi s’oppose cette position du témoin à un procès. Le témoin à un procès, selon le texte de Reznikoff qu’on a lu tout à l’heure, ne peut pas dire qu’un homme était « négligent », ce qui serait une conclusion, mais seulement comment cet homme s’est comporté. Et donc il s’agit moins de l’action de simplement voir, que d’une véritable action, non pas statique mais dynamique, qui serait opposée à l’exposé d’un simple préjugé, de quelque chose qui a déjà été jugé, déjà conclu ; il s’agit d’un acte de dévoilement actif dans le témoignage. La proximité ou l’approche est alors une attitude d’adresse, non pas une attitude isolée, qui se consacrerait à former des images statiques à distance dans une évidence simplement visuelle, optique ou oculaire, mais de quelque chose d’actif. Par exemple, Charles Bernstein a cité des poèmes concernant le métro, qui se distinguent nettement des poèmes imagistes qui constituent une image à distance, une image simplement contemplée, oculaire, et opposent donc le sujet, qui est en fait omis, qui est mis entre parenthèses, à l’objet ; tandis que dans les poèmes de Reznikoff il y a un rapport beaucoup plus dynamique, beaucoup plus actif entre l’observateur et les objets. Il s’agit donc d’une sorte d’intimité dans l’adresse, d’une entrée, d’une intrusion violente dans le matériau lui-même. Cela constitue une forme d’habitation, dit Charles Bernstein. Il oppose aussi cette position du poète à l’ironie, par exemple celle d’Eliot, â la distanciation par rapport au langage lui-même. Ce que fait Reznikoff c’est défaire, dépouiller le langage des distorsions symboliques et métaphysiques qui peuvent lui être imposées par la rhétorique, comme par exemple, chez Eliot. II essaie de le retrouver dans la plus grande neutralité possible. Et pour en revenir à la question de l’exil, Charles Bernstein note que, dans un poème, Reznikoff parle de la distance, de l’éloignement de la langue hébraïque. Le poème dit :

comme l’hébreu est difficile :

même les mots hébreux pour mère,

pain, soleil

sont étrangers.

« Comme j’ai été exilé de Sion. » Et cette distance, dit Charles Bernstein, n’est pas simplement quelque chose de constaté ou d’accepté, mais constitue au contraire un défi pour la poésie de Reznikoff. Le témoin en ce sens est donc quelqu’un qui est impliqué, qui prend soin, qui est en charge de quelque chose, qui est responsable. Il est en charge du langage et il est en charge du monde lui-même. Et le langage lui-même peut être considéré comme ce qui doit prendre soin du monde. À ce propos, Reznikoff aimait une formule Zen

concernant le témoin, qui définissait le témoignage comme « autoannulation, » « auto-effacement, » de sorte que le langage lui-même, l’événement lui-même parle seul, parle de lui-même. Et il appelle cela une autonomie moderniste du langage. Dans Testimony, ce qui intéresse beaucoup Charles Bernstein, c’est la structure de l’événement. La structure de l’événement, c’est une sorte de constellation faite de ces détails, une image composée de détails ; c’est-à-dire qui est produite par cette méthode, donc, de mise en série de détails, et qui n’est pas présupposée (par opposition, je pense, à l’esthétique imagiste). L’image est produite, elle n’est pas présupposée. C’est donc l’opposition même du sujet et de l’objet qui est remise en cause, ou qui est effacée par cette poétique dans cette proximité. Si bien que les autres formes de cette opposition observateur/observé, etc., toutes ces dualités disparaissent ; la distanciation et l’ironie s’effondrent, et l’observateur entre dans le monde observé lui-même à travers un processus de deuil participatif — c’est la formule de Charles Bernstein. Il est donc jeté dans le monde, dans l’événement comme témoignage, ou dans le témoignage comme l’événement lui-même ; et le poème, qui est donc ce témoignage comme événement, cet événement comme témoignage, dissout les polarisations objectif/subjectif, etc. L’événement émerge alors comme le processus de matérialisation du monde et du mot à la fois. Fonder l’Amérique elle-même, comme le disait au début de son exposé Charles Bernstein, par le texte de Testimony par exemple, cela veut dire : la découvrir, c’est-à-dire reconnaître ses racines et les reconnaître dans la violence, parce que Testimony est particulièrement consacré à des faits divers extrêmement violents ; retrouver ses racines parce que si ces histoires oubliées ne sont pas rappelées, on ne peut rien fonder. Une phrase de la mère de Reznikoff est citée à ce moment-là, qui disait : « Nous sommes une génération perdue. » C’est justement le geste des parents qui en appellent à une fondation, qui exigent une fondation en immigrant. Il s’agit donc de s’opposer plutôt que de se plier à l’indifférence d’un témoignage simplement juridique, et de s’opposer ã la distanciation qu’il suppose dans l’idée qu’on s’en fait habituellement. Fonder, cela veut dire donner un témoin à ce qui a été nié, oublié, au prix de la possibilité même de l’Amérique, c’est-à-dire de la possibilité même de fonder l’Amérique. Testimony est donc un monument aux morts, pourrait-on dire, ou un monument au sens littéral du terme, c’est-à-dire un acte de deuil et de souvenir. Le prix de la vie, le prix de toutes les vies qui sont rappelées dans Témoignage constitue une sorte d’économie poétique et psychique, dont le livre est, en quelque sorte, la comptabilité. Il s’agit de tenir une sorte de livre de comptes des vies. Il n’y a personne — je pense qu’il s’agit là d’une citation, il dit, « Il n’y a personne pour témoigner et pour s’ajuster à ce monde, sauf ici même. » Et encore : « Appeler les âmes perdues, Ô terre, Ô terre, reviens. »

(1) Il y a un paradoxe dans l’histoire de la poésie objectiviste : elle ne fut vraiment reconnue que plus d’un quart de siècle après sa naissance et l’influence décisive qu’elle eut alors ne suffit pas à dissiper le mystère qui l’entourait. Son acte de naissance est la parution, en février 1931, dans la revue Poetry de Chicago, d’un choix de poèmes présentés par Louis Zukofsky ; sous le patronage d’Ezra Pound, des poètes alors inconnus étaient rassemblés sous l’appellation d’objectivistes. Ils fondèrent une maison d’édition, l’Objectivist Press, où ils publièrent leurs œuvres. Ils étaient quatre : Louis Zukofsky (1904-1978), chef de file et théoricien du

mouvement, auteur de A, cycle poétique dont l’importance est comparable à celle des Cantos d'Ezra Pound ; Charles Reznikoff (1984-1976), auteur de Testimony, de nombreux autres livres de poésie et de romans ; George Oppen (1908–1984), auteur de Discrete Series, On being numerous, etc. ; enfin Carl Rakosi (né en 1903), auteur de Amulet, Ere Voice, etc.

Bien qu’ils n’aient pas signé de véritable manifeste, ces poètes se reconnaissaient dans une « esthétique » cohérente, résolument américaine, qui rompait avec l’imagisme. L’objectivisme met d’abord l’accent sur « l’objectification » du poème : « une appréhension complètement satisfaite eu égard à l’apparence de la forme artistique comme objet » « une écriture qui est un objet ou affecte I'esprit comme tel » (Zukofsky). Mais l’objectivisme propose aussi une attitude nouvelle devant la réalité : face aux « choses telles qu’elles existent », il prône l’abstention de tout jugement esthétique ou moral explicite. « Je vois une chose. Elle m’émeut. Je la transcris comme je la vois. Je m’abstiens de tout commentaire. Si j’ai bien décrit l’objet, il y aura bien quelqu’un pour en être ému » (Reznikoff). La poésie doit ainsi créer des objets, « choses parmi d’autres choses » pour qu’ils « existent dans le monde, l’affectent et se soumettent à son jugement » (Zukofsky). « L’important est que, si nous parlons de la nature de la réalité alors nous ne parlons pas vraiment de notre commentaire à son propos ; nous parlons de l’appréhension de quelque chose, disant si elle est ou non, si on peut en faire une chose ou non » (Oppen). La poésie doit rejeter les symboles et les images où elle se complaisait, elle doit rompre avec la métaphore, « dont le défaut est d’emporter l’esprit vers un “partout' diffus et de l’abandonner nulle part” (Zukofsky). À ce parti pris poétique sans concessions fait écho le célèbre slogan de William Carlos Williams : “No ideas but in things” (“Pas d’idées sauf dans les choses”).

Malgré leur radicalité (qui allait de pair avec leur engagement politique), ou peut-être à cause d’elle, les Objectivistes furent largement ignorés pendant trente ans, à tel point que deux d’entre eux (Oppen et Rakosi) cessèrent d’écrire. Ce n’est qu’à la fin des années cinquante qu’ils furent redécouverts. Ils furent une source d’inspiration décisive pour le courant de Black Mountain (Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Larry Eigner, Robert Duncan), mais ils nourrirent aussi d’autres recherches poétiques aux États-Unis et ailleurs — en France, par exemple. Cette seconde vie de l’objectivisme est loin d’être terminée. Constater son influence sur la poésie contemporaine ne dispense pas de l’aborder directement, et l’on commence à peine à mesurer son importance : l’objectivisme fut peut-être la réponse poétique la plus intransigeante à tous les avatars du Romantisme.

Pierre Alféri

Le 3e numéro de NOTES a été publié par Raquel Levy

dans le cadre de l’atelier cosmopolite å Royaumont

en juin 1990.

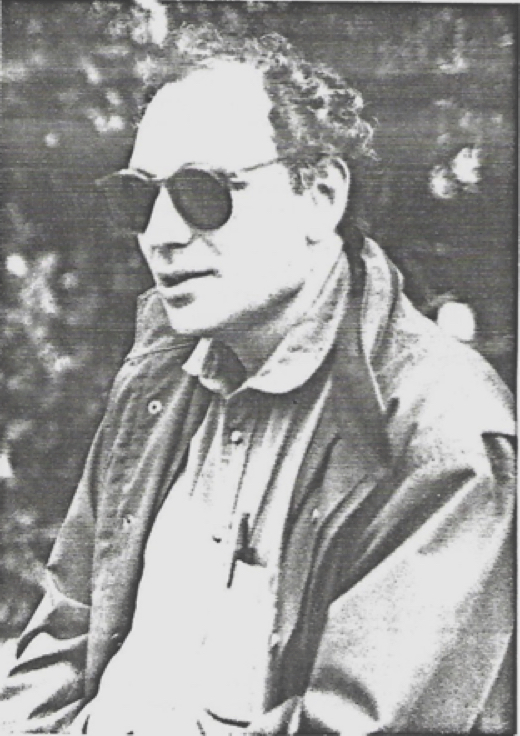

Charles Bernstein. Octobre 1989, à Royaumont.

Charles Bernstein. Octobre 1989, à Royaumont.